Walk

into the ASC on any given night during the school year and chances are you’ll

find a student pulling an all-nighter as they try desperately to finish an

essay that’s due the next day.

While it is obvious that the student has procrastinated on the assignment,

the next question that we might ask is why? As a tutor I have seen many intelligent, capable students

who wait until the last minute to begin writing a paper simply because they don’t

know how to approach the topic. They

lack the ability to develop a strong argument, which throws them off from the very

beginning and often leaves them frustrated and unsure of how to approach the

subject at all.

One

of the main problems that many students find with writing essays is the sheer

intimidation that they might feel towards writing something that is strong

enough to demonstrate their stance.

A key element in being able to do this involves understanding and

becoming adept at using argumentation, an issue that Ursula Wingate attempts to

tackle in, “Argument!” Helping Students Understand What Essay Writing Is About. According to Wingate, there are three

elements necessary to achieve successful learning of the concept of

argument. The first of these

involves the development of the writer’s ability to analyze and evaluate

different sources for content that may be useful in not only supporting the

writer’s position, but also in helping him come to that position in the first

place. Secondly, the writer must

develop a clear position in the argument. Oftentimes students may become so

overwhelmed by all of the information being received that they simply restate

what they have read without actually providing any analysis or even choosing a

positioning the matter. Finally

and perhaps most importantly, the writer must learn to present their position

to the audience in such a way that their argument is logical and makes sense.

How

then do we as tutors help to achieve these three different elements? In my own experience, I have noticed

these three different elements but have often felt unsure of how to go about

helping the student to fix them, as they are rather large concerns to

address. It is helpful then that

these different components seem to build upon one another; therefore it may be

useful to use them as a sort of guideline in deciding at what level to begin

helping the student. For instance,

one should note that the student cannot take a position on a subject if he has

not yet developed the ability to look at different resources and evaluate their

positions. In this case, the tutor

may start with the first component and help the student understand not only how

to analyze resources, but also how to critically think about how the positions

of these resources will affect their own opinion. Once the ability to analyze resources has been achieved, the

tutor may then move on to helping the student develop their own opinion. For many students, this may be a great

time to introduce a concept map as a way of helping the student understand how

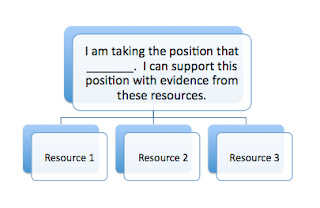

the resources they have analyzed are affecting their argument. This concept map could show the

position that they are taking and then have a number of different resources

that the student has analyzed that may be used to help support their

position. It could look something

like this:

After

this level of understanding has been achieved, the tutor may then move on to

helping the student achieve the third component of effective argumentation,

which is pulling their argument together in a cohesive, logical manner. In this case, the tutor may find that

the use of an outline will be of great benefit. While many students skip the outlining step, I personally

find it to be one of the most beneficial things that one can do in creating a

strong and coherent argument. At the

same time, this is also a good point in time for the tutor to help the student

in developing a strong thesis statement to anchor their argument. A rather

simplified sample outline may look something like this:

As

Wingate moves on to talking about how argumentation is learned, she notes a few

things that one must consider when thinking about how to address the components

necessary for teaching argumentation.

She cites work by Andrews showing that many students have difficulty

identifying conflicting viewpoints in the first place. In addition, she also talks about three

different patterns of difficulty as described by Groom. The first of these voices is known as

solipsistic voice and is characterized by the student’s tendency to use their

own experiences and opinions as part of their argument without actually

supporting these with elements from the literature. The second voice described by Groom is known as the

unaverred voice and describes a student whose writing becomes, “a patchwork of

summaries of other authors views.” (Groom, pg. 67, cited in Wingate) With the third voice, known as the

unattributed voice, the student takes propositions from what they have read and

make them sound as if they are there own without citations.

Knowing

the difficulties that many students face in developing their argument, the

tutor is better equipped to look for these different voices and to try to

ensure that the three elements necessary for argumentation are being

addressed. For instance, before a

student can take a position on a subject, they must be able to look to a

variety of different resources and pull information that will allow them to

understand each side and decide which one they find more favorable.

In

addition, it is also crucial that they student have the ability to analyze

these resources and understand how they can use them to support their position

rather than simply regurgitate them.

In addition, learning the characteristics of these three voices will

allow the tutor to spot the voice earlier and then to guide the student towards

how they can create a stronger argument.

With the solipsistic voice, it may very well be that the student’s

opinions and experiences on the subject that they are working with are

valid. It then becomes the tutor’s

role to help the student understand why they cannot just use their opinions and

how they can use evidence from the literature to support their opinions as a

way of making their argument stronger.

When addressing a student who is using the unaverred voice, the tutor

might attempt to help the student better analyze the resources that they have

found rather than just summarize them.

Here is a great opportunity to use the concepts of Bloom’s taxonomy to

help the student achieve a higher level of thinking. Finally, the student using an unattributed voice is also

likely to need help understanding how to analyze different positions as a way

of coming to their own opinion.

Again, the use of Bloom’s taxonomy to help the student analyze strong

and weak points of different arguments can help the student come to their own

opinion, after which the different pieces that have been analyzed may be used

to support their position.

In

tutoring, we talk a lot about global and local concerns. The lack of a strong argument is a very

important global concern that should always be addressed in students’

papers. While helping a student

develop a strong argument may seem like a daunting task, it is definitely achievable

when we have the right tools in our tutoring arsenal.

Works Cited

Wingate,

Ursula. “‘Argument!’ Helping Students Understand What Essay Writing Is About.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes

11.2 (2012): 145-154. Academic Search

Complete. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment